As a Loyola student, you have the opportunity to work alongside our talented professors to partner in collaborative research. Learn more about some recent research and projects currently underway.

Epidemiology and Control of Chagas Disease

Dr. Patricia Dorn and a team of undergraduate researchers focus on interrupting transmission of Chagas disease, a leading cause of heart disease in Latin America, caused by the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi, and transmitted by kissing bugs. Through investigating the kissing bugs, they improve control methods and prevent people from becoming infected with this deadly parasite.

Chagas disease is contracted when infected kissing bugs bite humans or animals, opening a wound and producing contaminated waste that enters the wound or mucous membranes and ultimately into the bloodstream. Dorn says reactions to the bite itself can range from slight to extremely severe allergic reactions called anaphylaxis.

Once it enters the bloodstream, the Chagas parasite attacks muscle tissue, especially the heart, and may not be detected for 10 to 20 years. By that time, Dorn says the damage is done and the treatment options are limited.

Dorn and her student researchers have traveled to Guatemala to hunt for the kissing bugs in homes, caves and other locations in order to conduct the groundbreaking research. They've also spent time in Latin America creating educational films to educate villagers with step-by-step instructions for implementing an ecohealth approach to stopping the transmission of the deadly tropical disease. In Latin America, 7 to 8 million people are infected with the Chagas parasite and 30 to 40 percent of those are doomed to life-threatening heart disease.

Recent reserach conducted by the team shows people in the Southwestern U.S. are encountering the “Kissing bugs” that harbor the parasite that causes Chagas disease.

Although the bugs don’t infect humans at the same rate as they do in Latin America, the free-roaming kissing bugs in the desert Southwest frequently feed on humans outside the confines of their homes. For example, in a recent test eight bugs tested had all fed on humans and three of these were also infected with the Chagas-causing parasite Dorn and her team study—something the scientists can tell by looking at the DNA in the bugs’ abdomens. Because some of the bugs harbor the deadly parasite, this could represent an unrecognized potential for transmission of Chagas disease in the U.S.

Effects of Rouseau Cane on Coastal Wetlands

For almost a quarter century, Loyola University New Orleans biologists and ecologists Donald Hauber, Ph.D., Craig Hood, Ph.D, David White, Ph.D., and several undergraduate honors students, have studied the origination and effects of the common reed known locally as Rouseau Cane on the marshes and coastal wetlands of southeast Louisiana.

Their findings, which detail the spread of this plant and its role in coastal protection, is found in a published study, “Genetic Variation in the Common Reed, Phragmites australis, in the Mississippi River Delta Marshes: Evidence for Multiple Introductions.”

“Rouseau Cane has dramatically increased in the coastal wetlands along the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts during the past century,” White said. “The species’ spread is mainly due to the introduction of new gene types from Europe. These invasive types are becoming more common in the interior marshes of the Mississippi River Delta, land that is extremely rich in nutrients.”

The Mississippi River Delta covers an area roughly 521,000 acres, but during the last 40 years, it has been significantly reduced due to lack of river sediment coupled with high natural subsidence.

P. australis is the dominant emergent vegetation in the Delta’s outer two-thirds and is believed to play a major role in stabilizing these extensive marshes by breaking wave action and storm surges from the open Gulf while also capturing and retaining river sediment. “This stabilizing role protects the diverse interior marsh communities that provide food and breeding habitat for wildlife, particularly birds,” said White.

In recent years however, the new European gene types of P. australis, have begun to expand into the interior marshes displacing food and habitat resources for wildlife. This new invasion into these inner marshes is thought to have negative impacts on sustaining the migratory and local wildlife.

In the study, Hauber, Hood and White identified several new DNA types of P. australis which were likely brought here by migratory birds, river currents or ships. These European types are increasing the species’ footprint in the delta at an alarming rate, according to White.

The researchers have been monitoring the spread of the Rouseau Cane through aerial views of the wetlands to study the impact from above.

White noted the massive impact of Hurricane Katrina on the wetlands. “Flying over the coast and the Mississippi Delta, it is a terrifying and powerful image because of what is no longer there and it proves to me that the city is more vulnerable to another significant storm surge than I previously imagined. If every citizen of Louisiana had this kind of flight opportunity, we’d be moving much quicker and with far more attention to protecting and restoring our coast.”

Flights have confirmed that the invasive types of P. australis is spreading throughout their research sites in the inner marshes of the delta. In a similar flight during the spring of 2006, White observed small areas of the invasive P. australis that are now much larger and spreading to other areas outside the delta. The Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill caused some coastal wetlands loss along the very margins of the delta’s shoreline, according to the researchers. "The total wetland loss in the delta is remarkably low as a result of the spill, though any loss is very troublesome,” White said. “The small amount of loss is partly due to the freshwater sheet flow that kept oil away from the delta freshwater wetlands, and partly because of the peripheral stands of the P. australis which became the frontline physical barrier to oil invasion inland.”

White, Hood and Hauber use photo images from wetland fly-overs to continue studying P. australis in their study areas. “The study of P. australis is central to the health and stability of the wetlands of the Mississippi River Delta,” said White.

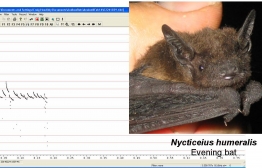

Mammal Biodiversity and Ecology

Biology students working under the direction of Dr. Craig Hood have helped assess mammal biodiversity, population ecology, and activity patterns of the Barataria Preserve of Jean Lafitte National Historical Park. Prior to Hurricane Katrina in 2005, Dr. Hood conducted his first formal mammal survey of the Barataria Preserve. This newest assessment shows comparisons between data and activity patterns.

Wetlands loss and the human impact on the landscape

When biology professor David White, Ph.D., takes his students into the swamp, he likes to go after dark. The wetlands south of New Orleans that he leads his classes through in canoes are full of snakes, spiders, and insects, and he will periodically tell students where to point their flashlights so they can reflect constellations of red alligator eyes.

He is not trying to scare anyone, he said, but to “demystify that nighttime world.” He likes to remind students that the drive down the interstate to the launching point is far more dangerous than slowly skimming in the dark through the reeds. He wants them to feel comfortable in the outdoors, and he uses the experience as a way to break down misconceptions about the natural world they study in biology class.

As they paddle, White discusses topics on ecology while natural manifestations of what he describes abound around them. The trips also provide students the emotional and spiritual sensations involved in being outdoors, which, White said, fewer and fewer of his incoming students have experienced.

The expeditions provide his students common points of reference that enrich classroom discussions. One honors student wrote to White and said she wished the trip had taken place earlier in the semester, because it was such an enriching bonding experience. The subjects his students study—like wetland loss, human impact on the landscape, and the interaction of organisms and their environment—become at once more tangible and complex, and his students come away with a more nuanced understanding and sincere appreciation of the natural world than any classroom lecture could provide them.

Algae Growth on Submerged Human Hair

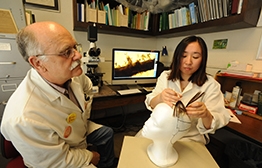

Ask The Algae: A biology student and her mentor devise a novel way to determine how long corpses have been underwater to aid law enforcement efforts.

Anyone who has watched mafia movies knows what a mobster means when he says he is going to make someone "sleep with the fishes." But this method of disposing of evidence on-screen has corollaries in real life, which can present real problems for law enforcement.

Currently, there is no good method to determine how long a body has been underwater. Such knowledge could potentially provide detectives important insight into when a crime was committed.Thanks to a Loyola student's honors thesis project, scientists may be one step closer to solving this conundrum.

Recent graduate Shelly Wu and her faculty mentor, James Wee, Ph.D., provost distinguished professor of biological sciences, monitored the growth of algae on submerged human hair and found its proliferation to be a potentially reliable time marker. For the project, Wu affixed standardized bunches of hair - clipped from her own head - to plastic foam mannequin heads she submerged in a freshwater garden pond and a brackish canal. She collaborated with James L. Pinckney, Ph.D., at the University of South Carolina to complete sophisticated measurements of the amount of Chlorophyll a - found in algae - on the hair, a method that could help investigators determine how long a cadaver has been submersed in water.

Wu documented her findings in a paper she co-authored with Wee and Loyola biology professor Craig Hood, Ph.D., which Wu presented at the 2013 Annual Meeting of the Botanical Society of America. She traveled from the University of Oklahoma, where is continuing her studies of algae ecology as a graduate student, to the 2014 Joint Aquatic Sciences meeting in May 2014 to present a follow-up.

By presenting at a scholarly conference as an undergraduate, Wu said, she gained yet another head start on many of her peers in building the complete set of skills required of a working scientist.

"A large component of being successful in science is presenting your work," Wu said. "It's how you establish yourself in the field, interact with and make an impression on experts. As an undergraduate, it was an enriching experience."

The experience Wu gained at Loyola put her ahead of many of her colleagues in graduate school - some, she said, have never conducted any independent research. As is true for many young Loyola researchers, the hands-on learning she engaged in here made a huge difference.

"It got me in the door," she said. "I was accepted to all of the graduate programs I applied for. If it wasn't for undergraduate research, I probably wouldn't be here."